As colonisation and settlement spread across Melbourne in the early 1850s, Victoria’s Gold Rush brought a swell of people from all over the country and the world. This meant that some areas, including the Crown land on either side of St Kilda Road, soon became a temporary home for people from a range of backgrounds and nationalities. This laid the groundwork for the building of an economically and culturally diverse community that would come together in Albert Park, Middle Park, South Melbourne and neighbouring areas in the years to come. Details of the ongoing cultural significance of the area for Traditional Owners have not been included below as these will be covered in a future instalment of the Celebrating Local Stories series.

Part 3 of Shrine to Sea’s Celebrating Local Stories series will paint the picture of how this assorted community came to be, and the challenges faced in those early years.

Word of Victoria’s Gold Rush quickly spread far and wide, and so immigrants from many nationalities, including Germans, Americans, Italians, and Chinese, came to Victoria in search of gold.

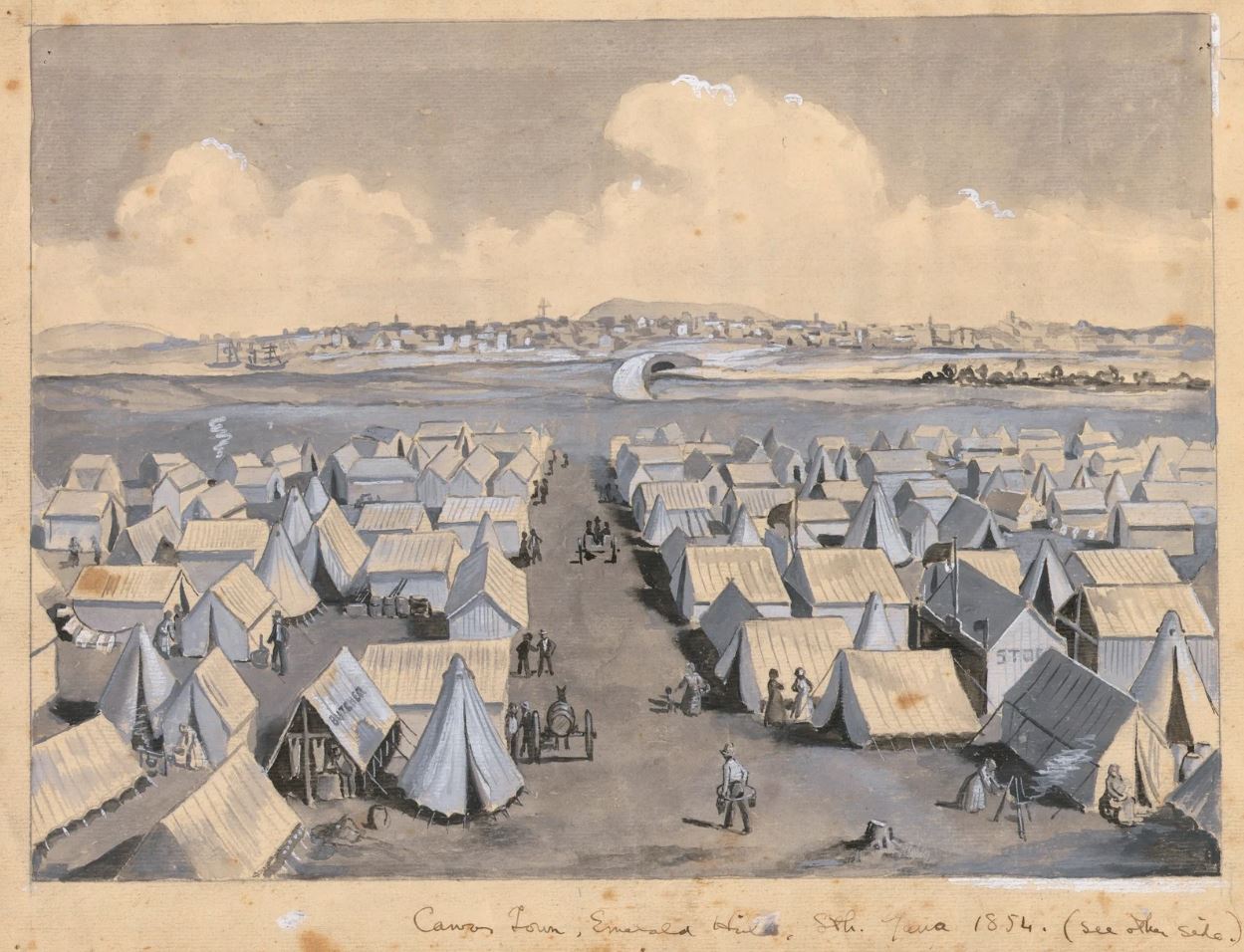

This surge of new arrivals created housing challenges, which resulted in a makeshift cluster of tents dubbed ‘Canvas Town’ springing up almost overnight on Crown land on either side of St Kilda Road.

Canvas Town, Emerald Hill, Sth. Yarra, 1854. Watercolour painting by Raymond Lindsay. (Source: State Library Victoria)

For years, the demand for residential land in the area far outweighed the supply because the low-lying land and extensive lagoons were a deterrent to settlement. But slowly, that began to change.

Forming the neighbourhoods

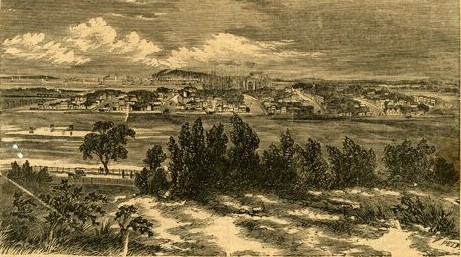

Property speculators around this time initially turned to the flats of Emerald Hill (in South Melbourne). Land in the area was sold for residential allotments from the early 1850s, with further development occurring in the 1860s. While the development was initially confined to the knoll of Emerald Hill, it later extended towards the Albert Park lagoon, though did not extend southeast of Beach Road (later Albert Road).

Emerald Hill from the St Kilda Road, 1863, showing a low hill rising from the otherwise flat floodplain of the lower Yarra. (Source: State Library Victoria)

The margins of the emerging Emerald Hill township still saw many people working the land nearby, with shepherds’ huts and fishing huts dotting the area.

Unfortunately, many of the houses in the area were of poor-quality, as the South Melbourne area was not bound by the City of Melbourne’s stricter building regulations. In contrast, the elegantly formed subdivision of St Vincent’s Place with its central landscaped garden reserve, was fronted with elaborate villa residences that appealed to the professional and merchant classes.

A mother and her children outside their home at 33 Danks Street, Albert Park n.d. (Source: Museums Victoria)

As the children of the gold rush generation began reaching maturity in the land boom years of the 1880s, Melbourne underwent extensive changes. There was a high demand for new housing and new suburban railways, which was met with significant residential development in the South Melbourne, Middle Park and Albert Park areas during the 1880s and 1890s.

On the west side of Kerferd Road, newly streets were established and lined with workers’ cottages. Much of the area on the west side of Kerferd Road northwest of Victoria Avenue remained working-class housing, while Middle Park on the east side of Kerferd Road was developed after 1890 with houses on larger blocks.

The working class and the poor

A large part of Albert Park was dominated by working-class housing that was largely tenanted. Their occupants worked in the neighbouring areas of South Melbourne and Port Melbourne, where there were numerous large workplaces, including on the wharves and the South Melbourne Gas Works, large factories such as Swallow & Ariell, and Kitchens’ soap factory. Roads and railways were also popular industries for employment.

Other primary industries included fishing and grazing. Fishing folk operated with a licence and sold their catch to the fish market or locally. Some hawked fish on the beach.

Local women often found work in the many factories of South Melbourne and Port Melbourne, while across the river in the city, they found work in the textile factories of Flinders Lane as well as in hotels and shops.

Convent of the Good Shepherd, Albert Park, comprising church, school, convent, laundry and refuge for ‘fallen women’ n.d. (Source: State Library Victoria)

The working class and the poor in this area often lived cheek by jowl and hence suffered plenty of hardships. The working-class housing was often considered substandard or ‘slum’ housing, but rent was still hard for tenants to make. There were very poor sanitary provisions, and much of the area was low-lying and prone to flooding.

With poverty also came the rise of social problems, which put women particularly, in vulnerable positions if their husbands resorted to alcohol or gambling, if they became violent, if they became ill and died, or if they deserted their wives. Without a single mother’s pension, welfare was scant and often only provided by churches and private benefactors. Some abandoned women were taken in by the Good Shepherd Sisters.

While there were periods of high employment and no shortage of work in good times, the poor were hit the hardest in difficult times. The economic depressions of the 1890s and 1930s saw extensive unemployment that had economic ramifications that some were unable to recover from.

Ethnic communities

As the gold rush brought in more and more immigrants, the original military barracks on St Kilda Road were converted to the Immigrants’ Home, while the Immigrants Aid Society Depot was located on the opposite side of the road.

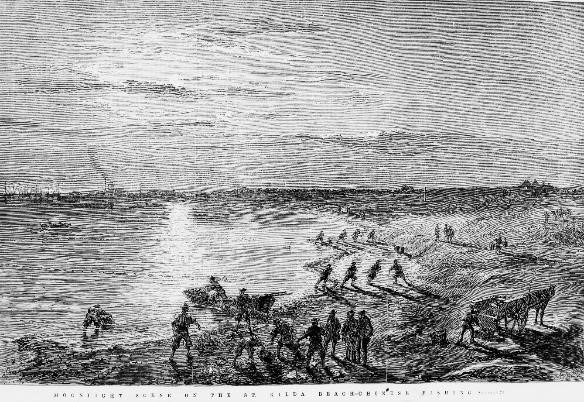

Several Chinese fishermen occupied the foreshore between St Kilda and Emerald Hill in the 1850s and in 1856, a Chinese Joss House was erected at Emerald Hill. The completed building, described as a pagoda or temple of worship by the press, was dedicated on 23 September 1856.

‘Moonlight Scene on the St. Kilda Beach — Chinese Fishing’; engraving by Robert Bruce, 1870. (Source: State Library Victoria)

The erection of the Joss House caused some controversy in the community, as many letters and articles suggested Christianity be made compulsory, and others proposed that foreign religions should be banned. However, some argued that no other body had the right to dictate what another should believe and that the existence of temples of worship in the colony was an opportunity for learning.

Following World War II, a large number of European immigrants arrived in Melbourne, many of whom moved into the South Melbourne area, notably Greeks and Italians. This brought greater diversity to the social and ethnic makeup of the area.

In 1959 the Greek communities from South Melbourne and Yarra Park established the Hellas Football Club, which was permitted to use the South Melbourne Cricket Ground as its home ground.

Hellas Football Club at the South Melbourne Cricket Ground c1960. (Source: South Melbourne Football Club website)

The broader area, notably St Kilda, was also influenced by Jewish culture in the post-war period. Although there were upwards of 50 Jewish families living in area in the years prior, it wasn’t until after World War II that St Kilda became a central point of social life for Jewish people in Melbourne.

The area became a bustling hub, with clothing stores, delicatessens and specialty European cake shops and bakeries springing up on Acland and Carlisle Streets in St Kilda.

In 1950 the Australian Jewish Welfare Society opened the Bialystoker Centre in Robe Street, St Kilda. It provided temporary accommodation for newly arrived migrants, and sponsored refugees to establish new lives.

A lasting legacy

Walking along the Shrine to Sea Boulevard area today, with Victorian- and Edwardian-era homes lining Kerferd Road, it may be hard to picture the challenging, working-class history embedded in the streets. However, through the nineteenth and twentieth century, poverty and hardship was the experience of many who lived in this area.

As for the area’s multicultural past, much of this has carried forward into the present in the surrounding areas.

The Jewish Museum of Australia, a place for all people to share in the Australian Jewish experience, is currently located in St Kilda, along with two synagogues.

There are also still some remains of Chinese fishermen’s huts at Middle Park today.

Many locals and visitors alike will be familiar with the South Melbourne Market, established in 1867, which still acts as a vibrant hub for shopping, entertainment, and food and drink from all around the world.

Though the South Melbourne, Albert Park and Middle Park areas have been transformed over the decades, the diverse history of those that formed the community years before helps us to further understand the building blocks of the neighbourhoods that we now enjoy today.

This is just one of many exciting historical stories from the local Shrine to Sea area. Stay tuned for more stories celebrating the area's exciting history.

Page last updated: 14/11/22